I was wrong about Bob Dole

A Larry story about apathy, the power of TV, and adulting your way into civic life

Even if you live under a rock, you probably know by now that Bob Dole is dead. This is sad news for Bob Dole and the people who knew Bob Dole. But it’s just news for the rest of us.

The thing is, news is an increasingly narcissistic undertaking in the social media age. You can’t just consume the news that a former leader of the Senate and Republican Presidential nominee died, you have to make it about you, somehow. There are several ways to do this.

Share your hot take about the deceased’s legacy. If your take is favorable, brace for backlash from their haters. If your take is unfavorable, brace for backlash from their fans.

Share the news without comment. Technically, this is a cop-out, unless you routinely share news without comment, in which case your whole social media strategy is a cop-out.

Share a personal anecdote about the deceased. Ideally, the anecdote humanizes the deceased in a way that adds a new dimension to their public persona, while simultaneously positioning YOU as someone worth following on social media.

If it wasn’t obvious from the title of this edition of Situation Normal, I’m going with option three. But I want to get a couple things out of the way before we begin.

First, I never met Bob Dole, nor do I have anything to say here about the man’s legacy. I’m writing about me (damn it), not Bob Dole, whose timely demise serves only to further my story. Second, I owe the people of Japan a sincere apology. They deserved better, and I’m really sorry for misleading them. Please forgive me, Japan.

OK, now that we’ve got that stuff out of the way, it’s time for the story.

The year was 1996. Braveheart won Best Picture, giving license to insufferable assholes everywhere to affect bad Scottish accents and shout, “FREEDOM!” Ironically enough, Alanis Morissette won a shit-ton of Grammys. And everyday, more Americans were getting on the Information Superhighway.

Oh, and 1996 was also an election year, which put an inordinate amount of pressure on fictional detectives to solve their cases.

Meanwhile, yours truly was a 19-year-old college student at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. Although I was studying political science, among other subjects, I wasn’t interested in the election, and I had no plan to vote. In those days, I had three strongly-held, poorly-executed-upon political beliefs.

We should save the planet, and ourselves, from environmental catastrophe by getting everyone to recycle and (somehow) stop burning fossil fuels

We should do more to guarantee equal rights for women, gay people, and minorities

We should legalize cannabis, man

Back then, these issues didn’t get much play in the national political conversation. Environmentalism was for nerds like Al Gore, but nobody thought a commitment to saving humanity from itself was a winning plank in a campaign platform. Equal rights for people other than straight white dudes got a lot of attention, but that attention was quickly turned into the “wedge issues” that fueled the culture war. And although Bill Clinton had inhaled, the thought of a candidate even talking about legalization was, literally, a pipe dream.

But the disheartening political climate was probably just an excuse for my disinterest in civic participation. Truth is, I suffered from a debilitating case of apathy, in part because I was young, and in part because it was the ‘90s and apathy was fashionable then. I was so apathetic that my most passionate political position was trying to convince friends that democracy was a “sham” and that we shouldn’t vote because, I argued, “our votes don’t matter.” I didn’t convince anyone (thank goodness), but I did prove to my dad that I was an immature jackass.

“You’re eligible to vote, and you’re voting,” he said. “This isn’t optional.”

“Technically voting is optional, Dad. Voting is a right, but it’s not mandatory. Read the Constitution.”

“Cut the bullshit, Michael. I’m not talking about that legal stuff. You’re my son, and we vote in this family—period. I don’t care who you vote for, but you are voting.”

I argued with Dad, but I knew it was a losing argument. I could be stubborn, but Dad had cultivated his stubbornness, among many other qualities, into a professional reputation for doing things his colleagues said couldn’t be done. That’s how Dad became the world’s best sound person, and it’s also how he became the first technical advisor to the Commission on Presidential Debates.

“Tell you what, you’re coming to the debate in Hartford,” Dad said. “Pick a couple of friends, ideally people who do care about politics, and I’ll arrange tickets.”

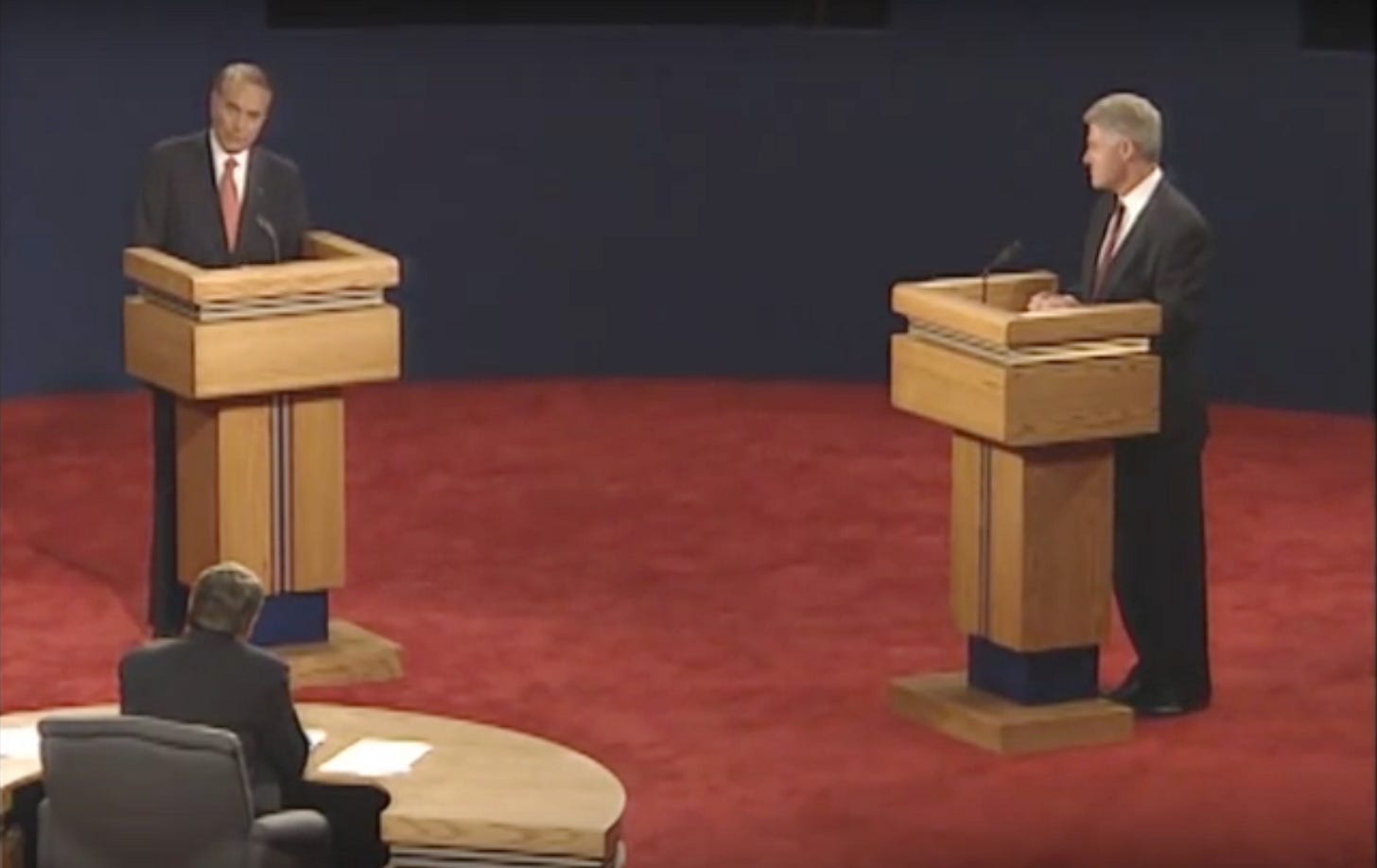

And so, one chilly evening, in the fall of 1996, a few friends and I bummed a ride with my roommate’s father, who drove us to the Clinton/Dole debate in Hartford, Connecticut.

I don’t remember much from the debate, so let’s just stipulate that both candidates dodged the moderator’s questions, fell back on their poll-tested talking points, and delivered the occasional pre-written zinger. That’s certainly how it appeared on television to hundreds of millions of people watching around the world.

But here’s something you might not know about the Presidential Debates. The press watch the debate on televisions from a room next to the debate hall. When the debate is over, they rush to “spin alley” to interview campaign surrogates, who also watch the debate on television, but in a different room. Through some combination of bullshit questions and bullshit answers, the people who watched the debates on televisions in rooms scattered all around the debate hall tell voters, who watched on television from home, who won the debate.

The audience that witnesses the debate live in the room is small, usually a few hundred people, or less. That’s why Dad wanted me there. He believed with all his heart that the greatest gift he could give his kids was a unique perspective on the world. At the time, I think he hoped that perspective would shatter his son’s cynicism.

As it turned out, it would take another twelve years for my cynicism to truly shatter. But that night in Hartford, as my friends and I left the debate hall, I caught a glimpse of just how special Dad’s gift to me—the gift of witnessing history—really was.

A reporter from NHK, Japan’s public media broadcaster, marched straight toward me and pushed a microphone in my face.

“Were you in the audience tonight?” he asked.

“Yes, I was there in the debate hall.”

“What do you do for a living, may I ask?”

“I’m a college student.”

“What do you study?”

“Politics and history.”

Satisfied that he had found a man on the street who had both witnessed the news live, and who possessed the relevant bona fides for providing some “insight,” the NHK reporter asked the only question that mattered.

“Who won the debate tonight?”

“Bob Dole,” I said.

Immediately, the NHK reporter pulled the mic away, turned to face the camera, and said something in Japanese to the audience back home. I don’t know what he said, but I recognized the words “Bob” and “Dole.” He said those words with enthusiasm, and I got the sinking feeling that my take had somehow become the take, at least as far as Japan was concerned.

The next day, I called Dad to tell him I was big in Japan. But Dad wasn’t an Alphaville fan, and so the reference their song, Big in Japan, flew right by him.

“What did you tell them?” Dad asked.

“I told them Dole won.”

Dad howled with laughter. My take didn’t conform to the conventional wisdom that was being distributed all over America the morning after the debate. (A few weeks later, America would ram that point home by re-electing Bill Clinton with 379 electoral votes to Dole’s 159). But sitting there in the debate hall, watching it live, Dole surprised me. In person, he didn’t seem quite as old, or nearly as cranky as the television talking heads said he was. I think I told Japan that Dole had won because he exceeded my manufactured expectations, whereas Clinton merely met them.

“It’s different in the room, compared to what’s on TV,” Dad said. “Most people don’t get to experience what you saw. They don’t see the behind-the-scenes.”

There it was—the sham of American democracy I had tried to warn my friends about. I wanted to stop Dad right there, bust out some Noam Chomsky, and ask how the Debates were any different from his other shows, like the Super Bowl, or The Oscars, or the Rose Parade. Wasn’t it all just entertainment, bread and circuses? And if so, why bother voting?

But for some reason I didn’t tell Dad I thought American democracy a sham. Maybe because I didn’t really believe that (I hope I didn’t, anyway). Or, maybe I didn’t say democracy was for suckers because in those formative dumbass years, when I tried on political beliefs the way you try on new pants, the one thing I truly did believe in was my dad, whose stubbornness easily bulldozed my apathy.

“Are you going to vote, Michael?”

“Yeah, I think so. I’ll vote. But I’m not happy about it. And I’m not voting for either one of those guys.”

“That’s fine. Vote for whoever you want. Just vote. You don’t have to like democracy, Michael, but that’s life in the big city, and being an adult means doing the right thing, even if you don’t want to do it.”

Our conversation shifted to the next debate, which would be a town hall format. That was Dad’s favorite format because putting microphones in the hands of the audience was the kind of live television high-wire act he lived for. I liked that format, I realized years later, because it’s as close as the Debates get to putting the demos in democracy.

“Oh, and one more thing, Michael.”

“What’s that?”

“You were wrong about Bob Dole. Nobody thinks he won, not even the Dole people.”

Hey!? Some of my best UCSC friends were immature jackasses! Not me, though. I was a totally mature jackass. Great story, Michael. I wish I could have known your dad. You write about him with affection. Sharron at Leaves

Lol! This is a great story. I think people are right about you. You kind of channel Dave Barry.... and the world definitely needs more Dave Barrys (also, I think Dole won, too). Thanks for the laughs!