Things aren’t going well. Or, maybe they’re going great. I wouldn’t know, and you don’t know either. One thing is uncertain: the Information Superhighway has led us into a clusterfuck that cannot be unfucked.

Last week, I wrote about the fires in Los Angeles. It was a disjointed post because the situation felt disjointed. I opened that post with a brief word about the Information Wasteland that swallowed Los Angeles. I’d like to elaborate. I hope it makes sense to you, but I fear it may not, as no two media bubbles are alike. Each of us, I worry, is trapped in our own private unreality.

Earthquake: Analog Disaster

I don’t talk much about the 1994 Northridge earthquake, mostly because it was fucking terrifying, and also because my extended family lost a mensch, and I don’t want my happy memories of Burt to get mixed up with that awful day.

I was asleep when the earthquake began. The jolt sent me flying vertically out of my bed. I hit the ceiling. It was a low ceiling, and I had a high bed, so maybe I flew three or four feet. It felt like a mile, though.

After the shaking stopped, we took shelter in my car. I was 16, so when I turned on the ignition, the radio was tuned to a local alternative rock station. A stoned DJ was freaking out, saying wild shit about how Hollywood was “gone,” and Venice was “gone,” and Westwood was “gone.” They weren’t gone. Almost immediately, the station cut to music, likely The Red Hot Chili Peppers, then came back with a different, sober DJ who calmly told us what he knew, which wasn’t much at that point.

Much later that day, or maybe the next day — I’m not sure because time blurs in disasters — we got a phone call about Burt.

Since the fires began, I’ve been thinking a lot about people who are getting those calls. Would they even pick up? Many people, especially younger people, don’t answer their phones anymore. It’s widely considered a good idea not to answer if it’s a number you don’t know.

At one point in my life, something called a “phone tree” would swing into action in these terrible moments. People would call other people and tell them the bad news. It was awful, but at least there was a human voice at the other end of the line, so you didn’t have to go through the awful part alone.

These days, it’s customary for the immediate family to take on the burden of notifying everyone else via Facebook. You don’t have to talk to anyone, which feels like a relief, until you realize that the expediency of social media robs us of human connection. In exchange we get Likes, Hearts, and whatever you call that sad-face button. Meanwhile, those receiving the bad news in their feeds will likely experience their first shot of grief wedged between an AI-generated thirst trap and some dickhead keyboard warrior cosplaying fire chief. I liked the old way better.

September 11, 2001: Disaster 1.0

I tried calling my dad to let him know I was safe, but these things called “long-distance” lines were jammed. Luckily, AOL’s dial-up service used local access numbers, which were still working in Brooklyn Heights that morning. I sent my dad an email, got a quick reply, and logged off for the rest of the day, maybe longer. See: time blurs in disasters.

I logged onto Facebook more times last week than I have in the past four years combined. I marked myself safe, and kept checking to see others, slowly, log on and mark themselves safe. Thank goodness. When I told a friend I thought Facebook was only useful for birthdays and marking yourself safe, he agreed, then added, “and to see if anyone you know died.” That’s an enormous amount of power to put in the hands of one man. Lucky for him, not for us, he also owns Instagram and WhatsUp, increasing the likelihood of getting Zucked (sorry for the pun, but not really) into an Information Wasteland.

Some attractions I saw in last week’s Information Wasteland: AI-generated photos of the Hollywood sign on fire, rumors about arsonists, posts shit-talking Los Angeles, post blaming the fires on DEI and wokeness. I believe the people who made these posts have the right to say what they said. My beef is with the platforms. If your algorithms are so great, if you know me so well, why on Earth would you think these are the things I want to read in the middle of a disaster unfolding all around me?

Of course, I heard equally unhinged comments all around my neighborhood on 9/11. Lies and ash were in the air that day. The difference: the shit-stirrers, fear-mongers, and cynical dipshits didn’t have digital megaphones, there wasn’t a business model that monetized their bullshit, and the metaphorical soap boxes they stood on weren’t platforms owned by some of the world’s wealthiest men. Also, I didn’t have to wade through the Information Wasteland to let people know I was safe and determine that my friends and family were also safe. I liked Web 1.0 better.

The Hills of Los Angeles Are Burning: Disaster 2.0

A few of the most frightening moments for this Angeleno:

The false alarms mistakenly sent to everyone in the county. I watched a local TV news team fact-check one false alarm on the air in real-time. Sitting on the couch, in that moment, I was grateful to have deleted every social media app, including Substack, from my phone. Can you imagine the clusterfuck of social media three minutes after a county-wide alert, as you’re trying to figure out what’s real, and if you need to bug out? I don’t want to.

The surreal night when it looked like the mayor had axed the fire chief. Legacy media didn’t have answers that night; the story, as they say, was still “developing.” Supposedly, nature abhors a vacuum. Maybe that goes to show you just how unnatural social media is. The medium adores an information vacuum; that night social media was a firehose of all the wrong answers.

The Kenneth fire & the night the Palisades fire nearly jumped the 405. For the first time in my life, I asked this terrifying question: will all three mountain ranges ringing the San Fernando Valley burn at the same time? Nobody talked about this on the local news, although I suspect many people shared this unspoken fear. I am grateful for sound judgement, level heads, and responsible news outlets. Spit-balling about the nightmare scenario on live air would’ve spread panic. Spit-balling about that nightmare on social media increased your chances of going viral.

You’re On Your Own

With apologies to Winston Churchill, here’s an unpopular opinion: gatekeepers are the worst way to disseminate information, except for all the other ways. I didn’t hold that opinion when I first got online in the 1990s. I didn’t hold it when I got my first job covering tech in 2006. And I didn’t hold that view during most of the Web 2.0 era. Actually, I’m not sure I totally agree with it now.

Open protocol information distribution systems are great, maybe the best thing that’s ever happened in the history of information distribution. But here, I’m talking specifically about email and podcasts (See Jaron Lanier’s Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now). What we call the internet, by which we usually mean the World Wide Web, remains a powerful toolset that, on balance, has improved life in immeasurable ways. The trouble is, social media is the internet for far too many people, which means too many people and too much information are trapped inside a wasteland.

I used to think you could just quit social media. I quit Twitter, and it stuck; I quit Facebook, but came back, reluctantly, when I heard a college friend had died. Now I realize social media will never quit you. What happens online doesn’t necessarily stay online; sometimes, it impacts the offline world in terrible ways. As an LAFD public information officer told the Wall Street Journal, “It takes people and time to track down or debunk social media rumors — it takes us away from doing more important things.”

What is so bleak about this moment isn’t the Information Wasteland per se, but the fact that there is no going back and little hope for what comes next. Or, maybe I’m just too jaded to see the next great digital utopia. Maybe the next-generation of platforms — Bluesky, Substack Notes, Mastodon, etc. — will scale & keep their promises. Wouldn’t that be nice? Maybe the investors in the companies that make those products will look at the ashes of the previous information dystopia and accept the relatively modest returns of a media company, rather than the 10x growth that is the rule in tech and the impetus behind the relentless march of enshittification (See Cory Doctorow’s essay Social Quitting). Maybe there’s hope somewhere between the guts it takes to invest in a product that might be a better information distribution machine and the greed that drives investors to want to own it all. Or, maybe, as my father-in-law would say, I’m wishing in one hand and shitting in the other, and we’ll see which one fills up faster.

Standing Watch

One of the few bright spots in the Information Wasteland this past week was a non-profit app called Watch Duty. From the Watch Duty mission statement:

Watch Duty is a non-profit, non-partisan, and non-government organization focused on disseminating public safety information in real-time from verified sources. Our service is powered by real people – active and retired firefighters, dispatchers, and first responders (not crowdsourced) — who diligently monitor radio scanners and collaborate around the clock to bring you up-to-the-minute life saving information. Our reporters undergo extensive training as well as background checks before joining our elite team.

Our mission is to publish only the facts that provide true situational awareness in case of emergency, without editorialization or prediction. We honor integrity and correctness over speed or sensationalism so we can build and maintain trust with not only our community but our first responders. As such, we adhere to a strict code of conduct for all of our reporting.

I can confirm that Watch Duty is a silver bullet in the Information Wasteland. The app helped millions of Angelenos last week.

It Takes Money, Honey

Operations like Watch Duty run on money. They have about a dozen full-time employees, plus several hundred trained volunteers. The money part should be obvious, but the everything-is-free ethos of digital hides the fact that good products and services require investments and revenue, if they are to be going concerns.

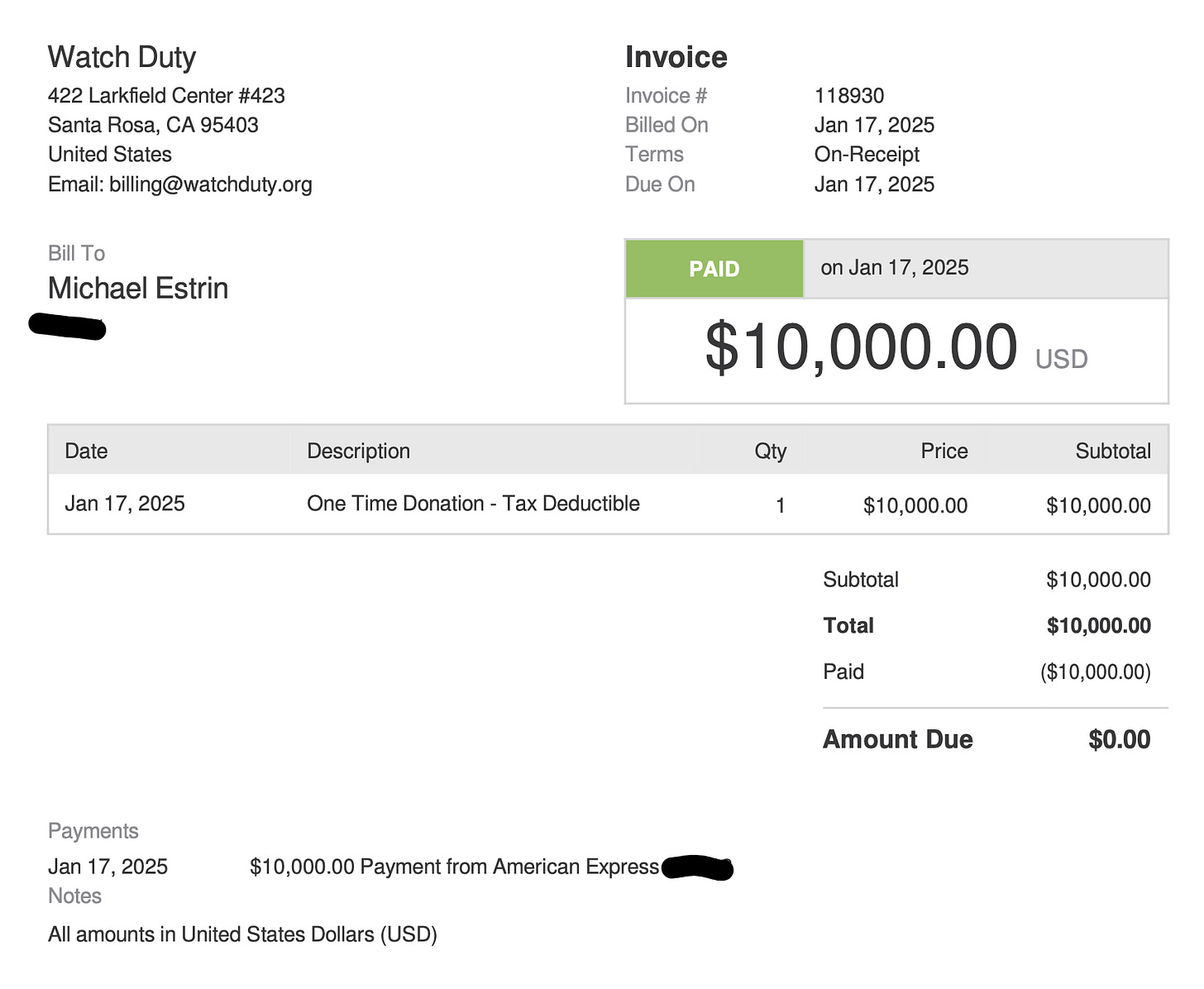

I recently came into some money as a result of the fires. The money came from a generous person who added a note to “stay safe.” The thing is, I am safe, and we don’t need the money. And so I find myself the steward of $10,000.

(No, really, I’m as shocked as you).

A lot of people need a lot of help. I’ve spent the past few days trying to figure out who to give the money to. There are no wrong answers here, but I was looking for the answer that felt most right. In the end, I decided to give the money to Watch Duty. That mighty non-profit saw LA through its most desperate, chaotic moments in the Information Wasteland, and I want that app to be there for the next community … when danger comes.

Housekeeping

I’d like to get back to normal at Situation Normal: slice of life humor, essays about cool books & movies, and occasional acts of absurdist journalism. With any luck, next week will be a return to form. Thanks for your patience & understanding.

Also, if you live in one of the 22 states where Watch Duty is currently available, you should totally download it. The app is free & it might just save your life, so it’s a pretty good deal.

I was just thinking yesterday how nice it would be to have the money and knowledge to create some kind of social media that didn't suck. Chronological timelines, good vibes, no AI garbage or algorithms. But I don't know if people would even truly go for something simple and ideal at this point after we've all been conditioned to the current way of things.

Thanks so much for promoting and donating to Watch Duty. It is literally a life saver. Santa Rosa-based, yay!! I’ve been a supporter since their beginning when they covered just three counties.